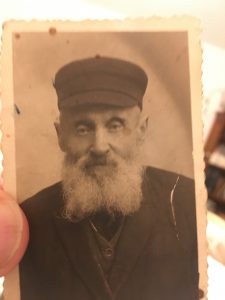

When you’ve survived a war that has destroyed your home and way of life, you’re left with little or nothing to remind you of your past. So it was with my parents. My mother had a gold lapis lazuli ring that her grandmother once wore and gave to my mother when she was nine years old. I have no idea how she retrieved it after the war or held onto it during the war. My daughter has it now. My father had absolutely nothing until an American cousin came to visit us and gave him photos of his grandfather and sister. Here’s the one of his grandfather.

I’ll never forget when my father held those photos in his hand for the first time. I’ll never forget his face, the tears and the mix of sadness and joy. Those photos were precious to my father even though they tell a sad story. On the back of the photos are some words in Yiddish. His sister’s photo simply gives her name. But on the back of his grandfather’s photo is a cryptic message: “Please listen to my dear plea. Children are kindness. Her father and grandfather from Ludmir.”

I’ll never forget when my father held those photos in his hand for the first time. I’ll never forget his face, the tears and the mix of sadness and joy. Those photos were precious to my father even though they tell a sad story. On the back of the photos are some words in Yiddish. His sister’s photo simply gives her name. But on the back of his grandfather’s photo is a cryptic message: “Please listen to my dear plea. Children are kindness. Her father and grandfather from Ludmir.”

My father had never met his first cousin before although he knew of his existence. He knew an uncle had come to America just after my father was born. My father assumed the uncle must have had children. When my father received a letter from his cousin in 1971 stating who he was and of his wish to visit, my father was both surprised and happy. He’d lost everyone in his hometown in the war save for one first cousin, who had immigrated to Israel. He longed for ties to real family no matter how tenuous.

The cousin came that summer. He was tall and thin with a full head of grey hair. Although younger than my father, he looked older. He was quiet and had a dark and sad mien. He was a bit effeminate. He had little to say and my father was disappointed in and exasperated by his newly found cousin. My father was a man’s man who pounded nails all day long for work. His cousin was probably gay and had an air of education and sophistication to go with his sadness. The two had nothing in common except their DNA.

After two days, my father wanted his cousin gone. My father needed to go back to work and that’s exactly what he did. But the cousin stayed. Every day he’d be a tourist and see what few sights Milwaukee had, come back for dinner and say nothing, and then go to his room, my brother’s old bedroom, for the night. By the fifth day, my father was gruff and slightly hostile to his cousin. He talked about kicking him out of the house, but my mother convinced my father to be tolerant if not welcoming. I was embarrassed by my father’s behavior, but also understood its source. He had impossibly hoped for the arrival of a cousin who shared his experiences and world view; instead he was hosting a soft American who seemed as Jewish as a bacon wrapped appetizer.

During the last dinner before my father’s cousin went back to the East Coast, I could sense my father’s relief. I could also sense that his cousin was used to being treated with hostility. It was a sad night, an example of how family can be hurtful. Then in the middle of the dinner, the cousin pulled out his wallet, took out two small photos, and handed them to my father. “I’ve been waiting to give these to you, but I didn’t know when would be a good time,” the cousin said.

My father took the photos. He instantly stood up from his chair. The photos were an emotional jolt. “My sister,” he said and started to cry. “Grandfather,” he said.

“My father gave them to me. I thought you should have them,” the cousin said.

”I can’t believe it,” he said. My father knew well the origin of these photos. In about 1935, his father wanted one of his daughters to immigrate to the US. She was about thirteen. Why did my granfather pick this one daughter out of all of his children? I don’t know. My grandfather wrote to his American brother to take this daughter into his home. I don’t have a copy of the letter. All I have are the photographs. But I can easily imagine the emotional content of that request. The message on the back of my great granddather’s photo tells me everything I need to know. “Please listen to my dear plea. Children are kindness. Her father and grandfather from Ludmir.” That photo and message were a desperate attempt to pull at heart strings.

After his cousin left, my father told me about receiving the response from his cousin’s father to the letter and photos. Life was hard in America, his uncle had written. He couldn’t afford to feed another child. My father told me my grandfather was despondent over this response. A little more than a half dozen years later, my father’s sister, father, grandfather and everyone else were murdered in the war.

We never saw the cousin again, but my father cherished the portraits he received, He kept them separately from our other photos, in the drawer where he kept his socks. I don’t know how often he pulled them out and gave them a look. I do know how strongly I feel a need to look at images of my own childhood. They are always a comfort, no matter how bittersweet those images may be.

Recent Comments