There are fewer than 10,000 Jews in all of Poland today. Before WWII, there were three and a half million. Today Poland is a monoculture of ethnic Poles who practice Catholicism. Jews, Ukrainians, Germans, Armenians, and Roma were once a major part of this country, which had a long history of uneasy tolerance of other cultures. Multiculturalism vanished in Poland after WWII. The towns Jews lived in throughout Poland and the rich culture they possessed are all gone. Jews are now zoo-like specimens in Warsaw and other cities. The Museum of the History of Polish Jews is an attempt to document a difficult past with a tragic ending.

I walked into the exhibits of the Jewish history museum, appropriately placed one level underground, and looked at the displays about the beginnings of Polish Jewry. The museum was all new, completed in 2014. Located within the boundaries of the old Warsaw Ghetto, it’s glass covered and elegant.

I walked into the exhibits of the Jewish history museum, appropriately placed one level underground, and looked at the displays about the beginnings of Polish Jewry. The museum was all new, completed in 2014. Located within the boundaries of the old Warsaw Ghetto, it’s glass covered and elegant.

The Museum of the History of Polish Jews was markedly different than the museum I had visited in the morning. The Warsaw Uprising Museum, contained in one of the few large pre-war red brick buildings left in Warsaw, was poorly lit and covered in black paint. This one, filled with calming mauve taupe paint and lightly stained wood, was meant to be welcoming. But I was wary.

The museum’s narrative begins with those in power in Poland happy to see Jews enter their land in the early part of the second millennium and making rules that allow Jewish merchants to prosper. I suppressed my impulse to talk back to the Jews described in the museum, “Don’t do this,” I wanted to say. “Don’t come. I know how this story is going to end. Badly. Horrifically. It’s a trap. Poles will hate you. Then Hitler will come to murder you.”

I looked around and watched the other visitors. They might as well have been in an art museum. Their faces were tranquil as they took in the multimedia displays. Did these people, mostly Polish adults and groups of kids on school field trips, know this tragedy in any detail? I didn’t think so.

I looked around and watched the other visitors. They might as well have been in an art museum. Their faces were tranquil as they took in the multimedia displays. Did these people, mostly Polish adults and groups of kids on school field trips, know this tragedy in any detail? I didn’t think so.

In the museum’s exhibits, anti-Semitism in Poland was an external force. Cossacks made pogroms. Germans made concentration camps. The dark past of conflicts between ethnic Poles and Jews was whitewashed as was the role of the Catholic church as a breeding ground for anti-Semitism. The creators of the exhibits had purposely made Polish-Jewish relations anodyne over hundreds of years of history. This museum displayed a selective narrative, one that wouldn’t upset any of today’s Polish leaders.

I’ve lived in the American South and have heard white Southerners in denial over their dark past. An American museum of slavery designed for their comfort and denial would employ an approach similar to what I saw in Poland’s Jewish museum. Slaves would be shown as happy people treated with kindness by their masters. No, ethnic Poles were not slave owners. They weren’t the cause of the annihilation of Jews in Poland. But their hatred of Jews was omnipresent and during the Shoah they were complicit.

I got one fifth of the way through the exhibits and started to cry. I couldn’t take any more of the eerie calm of the crowd and the exhibits absent of heart and foreboding. I walked quickly, almost ran, through the rest of the exhibit, went back upstairs and got a beer to calm myself.

I thought about another museum, one planned, but never built. The Nazis collected a great deal of Jewish memorabilia. Had they won the war and annihilated all of European Jewry, they planned to show 200,000 Jewish relics in a post-war Jewish museum of their own. The Nazi museum would have celebrated the annihilation of Jews and been scathing in its depiction of Jewish life in Europe. Certainly none of that was present in this Polish museum. But the types of artifacts shown in the Polish museum were identical to those the Nazis would have displayed.

It’s a sad and depressing fact that the state of Jews today in Europe is nearly the same as the the Nazi’s dark hope. Jews are essentially extinct throughout the Pale of Settlement. They are essentially gone in Germany as well. The Polish museum was inadvertently a museum of cultural extinction.

As I drank my beer (and had some duck and tzimmes), I thought of how I would design a museum like this one. Darkly painted, it would tell a story of hatred and the evils of anti-Semitism. But the museum I wanted was one that could never be built in Poland.

As I drank my beer (and had some duck and tzimmes), I thought of how I would design a museum like this one. Darkly painted, it would tell a story of hatred and the evils of anti-Semitism. But the museum I wanted was one that could never be built in Poland.

I heard my father’s voice in my head, the one that told me not to be a baby, but to be a man. “Be strong,” he’d say to me in Yiddish. I needed to stop brooding and see the rest of the museum.

I went back downstairs and walked through the exhibits a bit faster than most. The Jews portrayed in this museum were not a bad people. They were not greedy. They were not Christ killers. In the post-war period, they weren’t detested communists and communist sympathizers who destroyed the lives and livelihoods of ethnic Poles. All the awful anti-Semitic tropes present in Polish culture even today were as absent as the role that Poles played in the destruction of Polish Jewish culture.

Instead in this museum there was a nostalgia for Jews and their music and customs in Poland. The dire poverty of many Jews before the war and the threats they faced from Poles, both of which propelled Jews to dream of leaving Poland for Palestine, were ignored. In this history, the Jews came to Poland, flourished and then were washed away in a terrible externally driven tragedy.

Jewish scholars who played a role in the construction of this museum had to know they were helping to invent a narrative. But they had achieved a partial victory. Jews were shown to be worthy of sympathy. To have Jews depicted in a Polish museum free of negative stereotypes was major progress. Is a museum that tells lies by omission of value? Not for me, certainly. But I’d be happy if I knew for certain that one hundred years from now, Jews will be thought of with nostalgia in Poland as pleasant, dairy-restaurant creating, klezmer playing merchants and craftsmen.

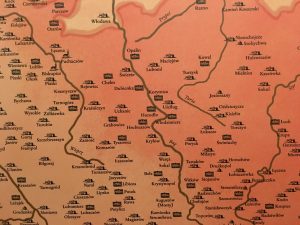

I was done with a generic and artificially sweetened history of Jews in Poland. I had to see my family’s history up close. First I needed to see my father’s Polish town, Wlodzimierz (center of map). It is now part of Ukraine and called Volodymyr Volynsky.

I was done with a generic and artificially sweetened history of Jews in Poland. I had to see my family’s history up close. First I needed to see my father’s Polish town, Wlodzimierz (center of map). It is now part of Ukraine and called Volodymyr Volynsky.

Recent Comments