I landed in Warsaw. On the bus from the airport to my Warsaw apartment, I looked around. The Germans destroyed Warsaw in WWII. Almost all I saw was 1970s Soviet era construction and newer. My father, who was kicked out of his home for lack of religious observance and had lived in Warsaw from 1936 until war broke out in 1939, would have found much of the city unrecognizable. But some parts had a nostalgic feel.

I walked around Warsaw for only a day and a half. Like my mother in Munich twenty years before, I had no need to linger. Warsaw was a dreary, yet utilitarian city. People seemed happy to talk to me, sometimes in Polish, more often in English. Warsaw reminded me of my own hometown, Milwaukee. The landscape was similar and the people were as unpretentious as the architecture. The similarities were not unexpected. Milwaukee had many Poles and the abundance of both Poles and Germans was why my father, unlike my mother, never learned English particularly well.

I walked around Warsaw for only a day and a half. Like my mother in Munich twenty years before, I had no need to linger. Warsaw was a dreary, yet utilitarian city. People seemed happy to talk to me, sometimes in Polish, more often in English. Warsaw reminded me of my own hometown, Milwaukee. The landscape was similar and the people were as unpretentious as the architecture. The similarities were not unexpected. Milwaukee had many Poles and the abundance of both Poles and Germans was why my father, unlike my mother, never learned English particularly well.

Milwaukee has one thing that Warsaw doesn’t. Jews. Tens of thousands of them. There are three times more Jews in Milwaukee than are left in all of Poland. In Warsaw, the only Jews I recognized on the street were Israelis on vacation. I ended up being a translator for two families for a bit. It was mentally exhausting to quickly flip between English, Hebrew and Polish. My parents flipped between three to four languages every day of their adult lives. I tip my hat to them.

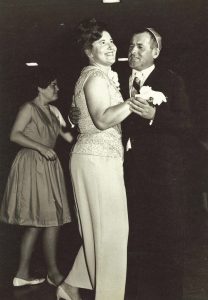

My father had lived in Warsaw as a teen when it was overflowing with Jewish culture. He loved his time there. He had a job as a furniture maker, a skill he had learned from his father, and made good money. He told me about the night life in Warsaw in the 1930s and the fun he had chasing girls. Big city life free of religion had been liberating.

My father had been to Warsaw during the war as well. In the Soviet Union in 1943, he was drafted into Stalin’s Polish People’s Army to serve on the front lines. He knew enough German to be enlisted as a translator for a Russian colonel.

In late summer of 1944, my father’s troop advanced with the Soviet Army all the way to the suburban Warsaw town of Praga on the east side of the Vistula River. The Warsaw Uprising – an attempt by the non-Soviet-aligned Polish Home Army to drive German troops out of Warsaw – was failing on the other side of the river. Shortly after the Soviet victory in Praga, my father’s arm of the Polish People’s Army was given the order to attack Warsaw and aid the Polish Home Army.

I’ve read many scholarly accounts of the Warsaw Uprising and the advance of the Polish People’s Army. I also have my father’s story. They are not at all the same. I wanted to know the popular history of the Warsaw Uprising. How did the Polish government want to portray this event? The facts are that the Polish Home Army and Polish People’s Army were both crushed by the Nazis, who then blew up Warsaw and turned its beautiful buildings into rubble. Everyone agrees with those facts. But the devil is in the details.

The Warsaw Uprising Museum, completed in 2004, tells a story of Polish militarism and courage. You’d think through most of the museum that the Uprising had been entirely successful. What was a quixotic attempt to unseat weakened Nazi forces from Poland’s capital is transformed in the museum’s displays, audio tracks and movies into a show of Polish force, determination, and pluck.

It’s standard operating procedure for nations to try to redefine devastating defeats as moral victories. Given my distaste for hyper-nationalism, I find such efforts unappealing. When I hear people shout “USA! USA!” I groan. Pride in one’s origins is understandable. Ardent belief in a nation’s superiority is both absurd and harmful. But Poles lost their nation for over a century. Perhaps they can be forgiven for their not uncommon strident patriotism and their desire to distort history.

The facts are that in 1944 the Polish Home Army was an army in name only. It was a resistance group, poorly equipped and undermanned. For the Polish Home Army to fight the Germans on its own was folly. The Polish government in exile knew it was folly. They needed a real military force to engage the Germans in Warsaw. But the Soviet forces on the other side of the Vistula River weren’t interested. Neither were Western allies, who had battles of their own to fight.

[Photo shows aerial view of Warsaw, more or less completely destroyed, after war’s end. Still from museum film.]

[Photo shows aerial view of Warsaw, more or less completely destroyed, after war’s end. Still from museum film.]

In September 1944, the Polish People’s Army was told by the Soviets to cross the Vistula alone so that it could have the glory of reclaiming its capital city. Now comes the part of the story of the Warsaw Uprising that isn’t in any scholarly book. It’s my father’s story.

Polish soldiers in my father’s troop were suspicious. Why weren’t the other Soviet soldiers going to fight as well? My father’s Russian colonel talked to him in confidence. “Tomorrow my soldiers will be slaughtered,” the colonel said. “Russian air cover will not come. My soldiers will die because we’ve already won this war and Stalin wants all Polish soldiers dead.” Stalin was looking ahead and wanted to avoid the possibility of a capable Polish military force challenging him after the war’s end.

This colonel’s prediction came true. My father stayed with his colonel and watched his friends cross the river and die. The Soviet’s betrayal in the Warsaw Uprising isn’t mentioned in the museum. Its focus is on the Polish Home Army, which is viewed heroically in Polish culture. The Polish People’s Army, in contrast, is commonly viewed by Poles as a Stalinist tool full of pro-communists and communist sympathizers. My father would vehemently disagree with this characterization.

I’d seen enough of Polish failure and death strangely turned into a moral and patriotic victory. I left the museum and walked through a rather depressing neighborhood of Soviet era apartments. I knew where my next stop would be: The Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

I’d seen enough of Polish failure and death strangely turned into a moral and patriotic victory. I left the museum and walked through a rather depressing neighborhood of Soviet era apartments. I knew where my next stop would be: The Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

Recent Comments